- Home

- Tracy L. Ward

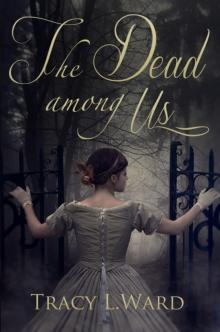

The Dead Among Us

The Dead Among Us Read online

The Dead Among Us

By Tracy L Ward

Smashwords Edition

ISBN 978-0-9881334-5-7

Copyright © 2014 by Tracy L. Ward

For my Nanny

Chapter 1

HEARKEN, oh hearken! let your souls behind you

London, 1868—Ainsley unwittingly held his breath, and would have turned away from the horrid sight were he not being closely watched by Inspector Simms. They stood in a yard behind a butcher shop, somewhere in the labyrinth of East London, the body of a boy, no more than fifteen, cradled in a damaged, weatherworn cart between them. The stone that made up the rear yard was swathed in a deep red blood, mostly pooled, although some trickled to the nearby gutters, where it would remain stagnant until a heavy rain would wash it further down the cobbles. The boy’s limbs were splayed outward from his torso, his face hidden behind one of his arms. So mangled was the corpse that Ainsley could not tell where the blood of the victim ended and the blood of the butchered animals began.

“Saving all the easy cases for me, I see?” Ainsley said, trying to hold back a sickness that churned inside him.

“I trust no other,” Inspector Simms answered.

Ainsley looked up, surprised at the detective’s words. Trust had been a hard-won battle that commanded a steep price. Of all the surgeons in London, Ainsley was certainly not the most experienced, nor could he claim to be the best. He had the misfortune of crossing paths with Simms at one of the worst times of the young doctor’s life and it was during that time that Ainsley proved his loyalty to the job, even above his own family.

A smile and nod passed between surgeon and detective.

“This is the fourth body, you say?” Ainsley asked, studying the cart and immediate area around the scene.

“Yes,” Simms confirmed. “I’ll have the others sent to St. Thomas so you can have a look at them.”

Ainsley internally winced at the thought of others but outwardly he nodded.

“And no one has moved him?” the surgeon asked, glancing to the constables who barred pedestrian entry to the yard.

“Correct.”

During the carriage ride over Ainsley had been told this was the third body found in such a way, limbs contorted, torso gutted, and organs missing. All the victims were children, homeless street rats, and none had been identified or claimed. This victim was the first boy and, judging by what Simms had already told him, he was the oldest.

“Do we have a name at least?” Ainsley asked.

Simms shook his head, an answer that only added to Ainsley’s work.

Ainsley’s survey of the scene expanded beyond the cart, the blood and the mud-smeared cobblestones, and he looked to the fences, the four-storey high buildings that surrounded them, and the myriad of curious faces peering down at them from above.

Despite the heavy presence of officers and detectives alike, local residents had scaled the rickety wood fences that circled the yard to peer keenly over the weatherworn wood to see the body. With great effort, Ainsley had for the most part ignored them, though his insides burned with anger at their insensitivity. So monotonous and dreary were their lives that they could not help but find some measure of enjoyment from the suffering of others.

Raising his gaze to the onlookers, Ainsley shook his head in disgust.

“Nothing can be done about that, I’m afraid,” Simms said, as if aware of Ainsley’s anger.

“Can we not cover the body?” Ainsley was indignant, his patience quickly running thin.

Simms pointed a finger to a nearby constable and instructed him to retrieve a blanket or canvas, something to shield the child from view. As they waited, Ainsley knelt down, bending his knees and resting his backside on his heels at the base of the cart where it had collapsed on the ground. His attention focused on the body, Ainsley fingered the boy’s torn clothes, threadbare and shredded at his midsection.

“Was this all he wore?” Ainsley asked without looking from the clothes. “Seems odd for March.”

On a hunch, Ainsley looked to the boy’s bare feet, blackened by the filth of the streets, and also saw signs of severe frostbite. The boy’s smallest toes on both feet were a deep black and did not clean when Ainsley ran his thumb on them.

“Where are his shoes?” he asked, shifting to look around the yard.

Simms shrugged. “He did not have any when Cooper responded to the call.”

“His shoes must be around somewhere,” Ainsley answered. “He’d have either pilfered some or been given some at the workhouse.”

Simms signalled for two constables to canvass the area for possible leads on the boy’s shoes.

Ainsley reached for the lad’s hands and carefully turned them over to study his palms. The boy had cuts running the length of his hands but they were not recent. Healed over and reopened repeatedly, most likely due to some repetitive task he had been assigned to perform. The nature of his work Ainsley could not guess, as street children were known to be hired as casual labourers, often changing tasks daily.

Two constables positioned themselves on either side of Ainsley, draping the blanket behind him, shielding him from those gathered at the fences and the tenement windows that faced into the courtyard. A homogenous moan rose from the onlookers, followed by a few shouts of protest.

“Give us a look-see!”

“Have a heart, Inspector!”

“Off with ye!” one of the constables shouted, raising a fist into the air.

Simms knelt down on the opposite side of the body and together Ainsley and the inspector moved to look over the boy’s face and head.

The boy’s hair had been cut haphazardly, and some patches to the scalp left red blotches on the otherwise white skin. Gingerly, Ainsley raised the boy’s lip to look at his teeth and noticed the front two were missing and his gums were red with blood.

“He was struck in the mouth,” Ainsley said, indicating the wound.

Simms nodded and wrote down something in his book.

“Send him to St. Thomas,” Ainsley said at last, and gestured toward the mess that was the boy’s torso. “I can tell you what’s missing, but I need my tools.”

Simms nodded.

Ainsley stepped out from under the blanket and motioned for the officers to lay it on the body. Simms took a step closer to Ainsley’s side, his eyes reviewing his handwriting, but Ainsley could tell there was more.

“There’s something else I should tell you,” Simms said, folding up his notebook and avoiding Ainsley’s gaze. “Have you read the papers this morning?”

Ainsley shook his head. He had been so firmly entrenched in his grief over the loss of his mother he had nearly forgotten a world outside Marshall House even existed.

Just then a man broke from the throng waiting at the main street. Pushing past the uniformed constables, he jogged between the buildings, heading straight for Simms. Unsure of the man’s intentions, Ainsley stepped forward, placing himself between the charging man and the inspector.

“No one is permitted back here,” Ainsley said, trying to be gentle as he pushed the man away. He noticed a small notebook in the man’s hands, a pencil in the other, and for a moment Ainsley thought him to be another inspector. However, the man bore no likeness to the other officers of the law Ainsley had come to know. Small and lanky, the man had excitability about him, unlike the strong, stoic stance of Simms.

With the man insistently trying to push past him, Ainsley curled his hands into fists and readied himself for a confrontation.

“Ainsley, no!” He felt Simms’s hand on his upper arm, pulling him back. “He’s known to us.”

“Theodore Fenton, Daily Telegraph and Courier.” The man presented a slender hand to Ainsley and when Ainsley didn’t res

pond in kind he grabbed for Ainsley’s hand anyway.

“A reporter?” Ainsley looked to Simms.

Simms exhaled and adjusted his jacket. “Theodore and I have known each other for some time.”

“Don’t be modest now. We’re kin, we are,” Theodore said with a jubilant smile.

Ainsley could not help but dislike him. Considering where they stood, there was nothing to be so joyous about.

“Theodore married my sister,” Simms explained, “Lord rest her soul.”

Ainsley saw a disparaging look on Simms’s face as he explained their connection. Such a contrast existed between these two men. Simms looked stern and ill-amused while Theodore Fenton had the look of a simpleton, unaffected and most likely unaware of the emotions happening all around him.

“We’ve got another one, have we?” Theodore asked, stepping past Ainsley to look at the scene. The boy had been covered and Theodore started to crouch down, as if to raise the sheet, when Ainsley grabbed his arm.

“Should I escort you out?” Ainsley asked. Kin or no kin, this man had no right to traipse all over their crime scene.

Theodore looked from Ainsley’s hand and then to Ainsley’s face. “I haven’t seen you before,” he said, shaking off Ainsley’s hand. “Are you a transfer from another division?”

“He’s a specialist,” Simms answered quickly. “Go on now, Theodore. I’ll give you what you need in a little while.” Simms waved in a nearby constable and pointed to Theodore. Instantly, the constable knew what was asked and went to Theodore’s side.

“Don’t mean to intrude,” he said as the constable grabbed him by the underarm. “You and your men have much work to do to catch our Surgeon.” Theodore’s voice grew fainter as he was escorted from the scene.

“Surgeon?” Ainsley looked to Simms.

“That’s what I was trying to tell you,” Simms explained. “The papers have taken to calling him The Surgeon on account of what’s being done to the bodies.”

“That’s horrendous. No self-respecting surgeon would ever perform such acts!”

Simms shrugged. “You and I share a commonality; our professions are equally untrusted.”

Ainsley grimaced at the thought and rubbed his forehead. The public’s mistrust of the medical profession held fast, it seemed. Judged as labourer and therefore less respectable than a physician, Ainsley’s position at the hospital offered him neither glory nor riches and now he might well be lumped in with the worst kind of criminal.

THWACK!

Ainsley glanced up; the sound of the butcher’s cleaver meeting the wood block at the back door of the shop stole his concentration. The resounding chop, chop, chop of the knife making quick work of the hunk of meat on his butcher’s block held Ainsley in a trance.

Four victims, all children. Murdered, mutilated, and discarded. To what end?

Unblinking, Ainsley stared at the cleaver’s movements and then watched as the discarded bones were slipped into a bucket alongside the table. And that’s when Ainsley saw two eyes, crouched in the shadows just beyond the butcher’s table, staring at him.

It was a boy, no more than twelve, with the ruddiness of the streets smeared into his red, cracked cheeks. No, not staring at him, Ainsley realized. The boy was mesmerized by the body and was not aware he was being watched by anyone. Ainsley saw a steady stream of tears trailing down the boy’s face.

“Doctor?” Inspector Simms asked.

The boy’s eyes grew wide and shifted, finally seeing Ainsley and knowing his position had been discovered. Jumping to his feet, the boy turned and ran, slipping through a hole in the fence boards.

“He knows him!” Ainsley yelled, pointing in the direction the boy had fled. And then, realizing he was the only one who had seen the child, Ainsley took after him. Slipping through the fence, he was just able to see the boy running full hilt down an alley and into the main thoroughfare, already bustling with morning traffic.

Ainsley had to turn his shoulders to slip through the two brick walls on either side and this slowed him down considerably. Once on the kerb Ainsley thought he had lost him, a large coal cart rolling by and narrowly missing his toes, until he caught sight of the boy farther down, turning a corner.

“What is it?” Simms appeared beside the young doctor, out of breath but determined to keep pace.

Ainsley pointed but kept moving in the direction of the fleeing child. “He knows our John Doe.”

The boy weaved skillfully through the mass of pedestrians while Ainsley struggled against the current, unable to manoeuvre as easily as the child.

“Wait!” Ainsley called, realizing he could not catch the boy on foot.

The boy looked back but did not alter his speed and everyone in the vicinity looked disinclined to help a bobby catch their equal.

“Better pick up yer feet!” a man yelled at Ainsley from a stoop. “He hasn’t much mind to wait for ye.” His joke incited laughter from many around but it lit a fire under Ainsley, who dug his heels in and began pushing his way through the crowd.

“Wait!” he called again fruitlessly.

At the corner, Ainsley narrowly missed being tromped by an approaching team of horses hitched to a carriage. The team’s driver shouted obscenities as he rolled passed. Through breaks in the carriage traffic, Ainsley was able to see the boy turning left into an alley. A few paces away from him, Ainsley could see a gateway into a courtyard and reasoned the alley must lead to the same row of yards.

Running across the street, Ainsley pushed through the gate and ran through backyards of mud, discarded waste, and cesspits. He crept through holes in rickety fences or scaled them easily since they were dilapidated so badly.

There was no sign of the boy and just as Ainsley slowed his pace, he looked to the closest alley and saw him, leaning against the bricks and panting heavily. Their eyes met at the same time and though the boy turned to run again, Ainsley was within a few paces of him and was able to grab the boy’s shoulder.

Struggling against Ainsley’s strong hand, the boy tried hitting him and wriggled against his captor. His desperation to get away was so pronounced Ainsley was almost knocked off his feet.

“Stop fighting me!” Ainsley said through gritted teeth.

“Let go of me!” the boy yelled. He tried to plough forward but Ainsley caught him at his midsection, hoisting him in the air with his arm. When Simms arrived, out of breath and chagrined, Ainsley was grateful for the secondary presence.

A groan escaped the boy’s lips as he flailed. “Don’t you know who my father is?”

“Who is he then?” Simms asked, through tight inhales of breath.

“A man of business!” the boy yelled, nearly spitting in Simms’s face as he crouched before him. “And when he comes back—”

Simms waved a dismissive hand and straightened his stance. “Ah,” he said turning.

“It’s true!” the boy yelled, pulling against Ainsley’s tight grip.

“You knew that boy,” Ainsley said, moving the boy to the brick wall behind them so he and Simms could question him at the same time. “The one killed behind the butcher’s.”

The boy stopped his struggling and Ainsley eased up on his grip, realizing both of them were weary and out of breath. He kept a steady hand on the boy’s shoulder, pressing him into the wall.

“You knew that boy,” Ainsley said again with increased force.

The boy just turned his head, refusing to look Ainsley in the eye, his desire for storytelling suddenly nonexistent.

“Why were you running?” Ainsley asked, his annoyance evident in his tone.

Just then, a uniformed constable entered the mouth of the alley and jogged his way to them. He waited to the side, blocking the exit from the alley.

The boy folded his arms over his chest and refused to look at Ainsley, no matter how the young doctor moved in front of him to keep eye contact. After a few moments of this, Ainsley turned to Simms. “Take him back to the workhouse,” he said.

; “I ain’t at no workhouse!” the boy yelled.

“Cooper.” Simms took hold of the boy, seizing him under the arm, and passed him along to the assisting constable.

Cooper held him as Ainsley crouched down in front of him. With threadbare clothes and oversized boots, the boy looked in no better circumstances than the boy they had just found dead.

“Give us the address then,” Ainsley demanded. “Your father can clear this up.”

The boy hesitated and Ainsley smiled.

“Thought so.” Ainsley stood straight, aware of how he towered over the child, and slipped his hands into the pockets of his trousers. “Mind telling me why you took off?” he asked.

The boy just looked away.

“What’s his name?”

The boy’s lips pinched into a thin line and his jaw tightened.

“Who is he? Your brother? A friend to pilfer with?”

“We ain’t no pickpockets.”

Ainsley laughed. “Then what is it?” he asked. “It is in this gentleman’s right to arrest you for impeding an investigation but if you can prove you weren’t involved, we can let you go.” Ainsley shrugged at the simplicity of it. “Unless you had something to do with this.”

“He was my friend.” The boy began to struggle but the constable tightened his grip.

“From where?”

Again the boy hesitated.

“Tell him!” The constable pulled the boy’s arms tighter at his back and the boy winced from the pain of it. The brutality of the act did not sit well with Ainsley. When tears began to streak the boy’s face in silent protest Ainsley raised his hand.

“Ease off a bit,” he said. Ainsley tried to look into the boy’s eyes but he just turned away, this time down, as if trying to wipe the tears on the remaining threads of his shirt.

Ainsley turned to Simms. “Where is the nearest workhouse?” he asked. “The boy must be known to them.”

The constable cocked his head to the south. “One down on Harbinger.”

“I told you I don’t belong to no workhouse!” the boy protested.

Mercy Me

Mercy Me Shadows of Madness

Shadows of Madness Sweet Asylum

Sweet Asylum Dead Silent

Dead Silent The Dead Among Us

The Dead Among Us Prayers for the Dying

Prayers for the Dying